Key Takeaways

- Madeleine Smith stood trial in 1857 for the murder of her former lover, Pierre Emile L’Angelier, becoming a subject of public fascination.

- The relationship between Madeleine and L’Angelier was secretive, with passionate letters that ultimately put her future at risk.

- L’Angelier’s death from arsenic poisoning led investigators to Madeleine, who had previously purchased arsenic, making her a prime suspect.

- Despite the scandal, the court ruled ‘not proven,’ and Madeleine continued her life, marrying George Wardle and later moving to New York.

- The case reflects Victorian society’s obsession with crime and the complex interplay between beauty and morality, as illustrated by Rossetti’s remark on Madeleine.

In 1857, a twenty-two-year-old woman stood trial in Glasgow for murdering her former lover, and Victorian Britain did what it does best: turned scandal into spectacle.

Her name was Madeleine Smith, and she was not only accused; she was watched. Reported on. Speculated over. Consumed in newspapers the way we consume true-crime documentaries now, except with more soot, more sermons, and far fewer guardrails.

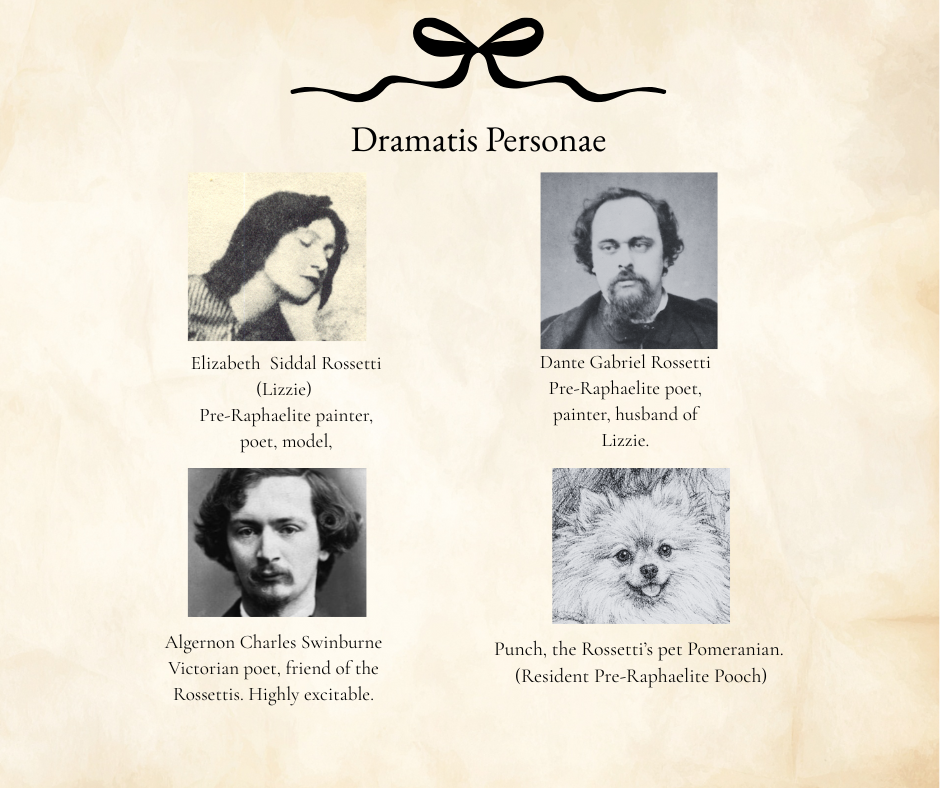

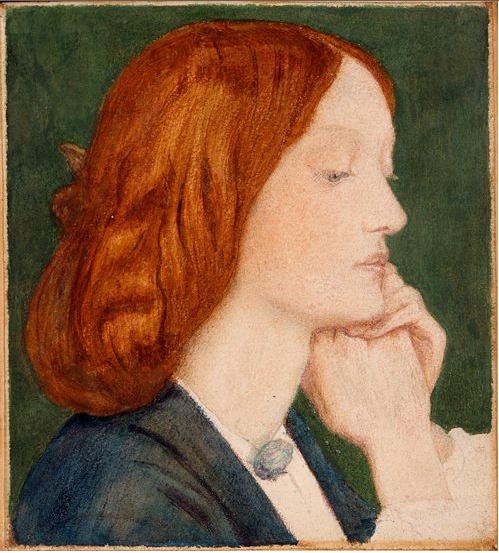

And somewhere down in London, in the orbit of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti heard about the case and delivered a remark so Rossettian it feels like a shard of his personality in a single line:

“you wouldn’t hang a stunner!”

(“Letters of D. G. Rossetti,” Atlantic Monthly, vol. 77)

Rossetti used “stunner” often, his favorite shorthand for beauty with impact, beauty that almost feels like a force. But here, the word lands with a strange shiver. It’s funny in that appalling way men can be funny about women in danger. It’s a compliment that doubles as a verdict: she’s too beautiful for consequences.

Which is, of course, its own kind of sentence.

Madeleine Smith and the Secret Romance

Madeleine was the daughter of an upper-middle-class family. Respectability was part of her furniture. Then she met Pierre Emile L’Angelier, a clerk at a shipping firm, who was low income, with uncertain prospects, and, crucially, not “acceptable.”

So they did what so many people do when a relationship can’t survive daylight: they made it a secret.

There were letters, of course. Dramatic, poetic, deeply Victorian love letters, full of the intensity that feels like forever right up until it doesn’t.

Their relationship became sexual, and they wrote about it openly to each other. That detail matters, because it becomes the lever that could ruin her.

Because once Madeleine’s feelings cooled and once her parents introduced her to William Minnoch, a suitable match in every social sense, L’Angelier suddenly held something dangerous:

He had her words. In ink. In her handwriting.

And he could use them to destroy her future.

Arsenic, the “Poison Book,” and a Trail in Plain Sight

When L’Angelier died of arsenic poisoning, investigators found Madeleine’s letters among his possessions, and the case snapped into a shape that the public could follow with relish.

There was also the practical horror of proof: it was established that Madeleine had purchased arsenic twice and signed the “Poison Book” at the time of purchase. An ordinary administrative detail that, in a sensational trial, becomes a spotlight.

The press seized the story. In The Invention of Murder, Judith Flanders describes the appetite for this kind of coverage and the protective language used around “good families,” a tone that tries to maintain decorum while the public crowds in for a better view. (You can almost hear the polite panic in lines like, “We fervently trust that the cloud over her head… may be speedily removed.”)

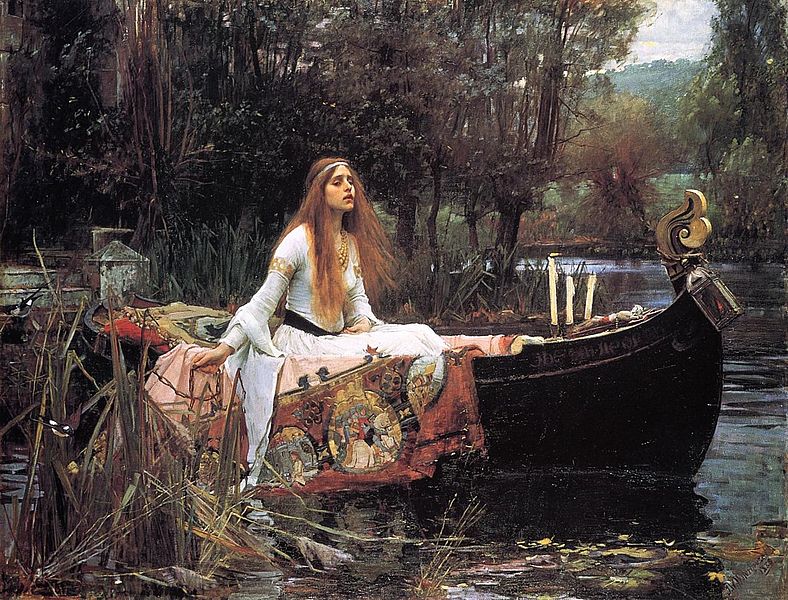

And the Pre-Raphaelite circle, so steeped in sympathetic Guineveres and Ophelias, so practiced at painting women as tragic and tender, followed too. It’s easy to imagine how Madeleine Smith might have been folded into their emotional imagination: a young woman “led astray,” cornered by the consequences of desire, punished by a society that loved to moralize after it had finished gawking.

Hence Rossetti: too beautiful to hang.

“Not Proven”

In the end, the verdict was “not proven.” Madeleine was released.

She left Glasgow. She did not marry Minnoch. Her life continued, but not as it had been. Notoriety has a way of becoming a shadow that follows you into every room.

And here is the twist that feels almost designed for a Guggums post, one of those strange little stitches connecting art world circles to scandal-world headlines:

In 1861, Madeleine married George Wardle, a manager at Morris & Co., a man Rossetti and his circle knew well. Rossetti later wrote a satire, The Death of Topsy, in which Madeleine poisons William Morris with coffee. (Victorian men had many ways of processing their anxieties; satire was one of their safer outlets.)

Madeleine and Wardle separated in 1889. She later moved to New York, remarried (to William Sheehy), and lived until 1926, long enough for the scandal to fade into “story,” the way public hunger always eventually moves on to the next thing.

She may never have known that a famous painter/poet weighed in on her fate with a breezy line about beauty and execution.

Why the Victorians Couldn’t Look Away

The Madeleine Smith trial sits inside a larger Victorian obsession: murder as mass entertainment.

There was a market for souvenirs of hangings. People bought pieces of the execution rope. Penny publications, called penny bloods and penny dreadfuls, fed a public appetite for villainy, gore, and moral panic packaged as thrill.

And that appetite didn’t vanish. It evolved.

It helped build the runway for sensation fiction and the detective story, genres that still shape what we frequently watch and read today.

The Mystery Lineage (and the Pre-Raphaelite Overlap)

Victorian crime culture helped produce the fictional mysteries we now treat like comfort food… cozy, macabre, brainy, addictive.

And in that lineage, you can find flickers of Pre-Raphaelite connection:

- Wilkie Collins, friend to Millais, gave us The Woman in White and The Moonstone, stories full of identity, concealment, and dread disguised as domestic order.

- Mary Elizabeth Braddon gave us Lady Audley’s Secret, a sensation novel with a deliciously painterly awareness of surfaces and the violence they can hide.

- Sherlock Holmes became the enduring Victorian detective, endlessly reimagined, and Holmes’s world even brushes against the Pre-Raphaelite orbit through the shadowy figure of Charles Augustus Howell, often cited as a model for Doyle’s villain Charles Augustus Milverton.

What I love about these overlaps is that they reveal something the Victorians understood instinctively: beauty and danger are not opposites. They are often co-conspirators. The prettiest room can hide the darkest story. The most “respectable” household can be the one that needs the most careful looking.

What Rossetti’s “Stunner” Line Really Exposes

On the surface, Rossetti’s quip is easy to repeat. It’s witty, scandalous, irresistibly quoteable.

But underneath it, there’s an uncomfortable truth: Madeleine’s beauty became part of the public argument about what she deserved. As if appearance could cancel out culpability or amplify it.

As if a face could be a defense.

As if a woman’s fate could be weighed on a scale where one side is morality and the other is the aesthetic pleasure she provides.

The Victorians loved to paint women as symbols. They also loved to punish them for being human.

And Madeleine Smith, whatever the truth of what happened between her and L’Angelier, became a perfect vessel for that contradiction.

She was a scandal.

A story.

A stunner.

A warning.

And, like so many women in Victorian culture, she became legible to the public in ways that may have had very little to do with who she actually was.

Which is exactly why she still haunts the imagination.