I’m drawn to the Pre-Raphaelites the way you’re drawn to read the last line of a letter again, in case you missed what it really meant the first time.

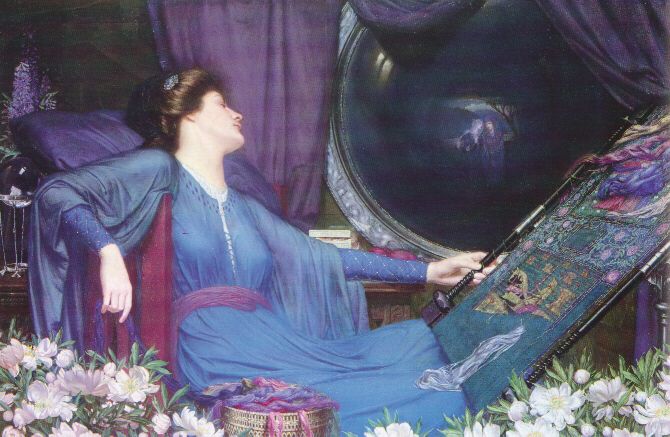

Their paintings do not simply depict beauty; they brood over it.

They make an atmosphere you can step into. All that abundant hair and bright light, flowers heavy with meaning, faces caught between longing and restraint.

Nothing is quite innocent in them, not a ribbon, not even a hand half lifted in a doorway. I look at their work and feel part enchantment, part unease. It’s as if the canvas is not only showing me a scene, but quietly insisting I remember something I have forgotten.

What draws me to the original Brotherhood, in particular, is their audacity. Their stubborn refusal to accept the approved version of beauty.

They were young, sharp edged, and convinced that truth lived in details everyone else had learned to blur. They captured the exact veining of a leaf, the depthof a shadow, the raw clarity of early light.

They looked backward to find a language that felt more alive, yet what they made was not nostalgia so much as a kind of defiance.

Even now, you can feel it under the paint, the sense that they were not merely making pictures but building a world they intended to inhabit, whatever it cost.

And then there is Elizabeth Siddal: my long standing fixation, my artistic north star. I found her first as an image, as most people do: a pale girl in a painted story, suspended between beauty and tragedy.

But the longer I looked, the more I felt the cruelty of that suspension. It struck me how easily the world makes a symbol out of a woman and calls it understanding. I kept following her trail: the poems, the sketches, the sharp silences where her own voice should have been louder.

For more than twenty years I’ve researched her because she refuses to stay flat. Each time I think I know her, she reminds me that the real story is not the one we repeat. It’s the one we’re still learning how to see.

In the end, it’s all the same pull. The Brotherhood fascinates me for its fierce, youthful insistence on seeing truly, even when truth was inconvenient. And Elizabeth Siddal holds me longest because she resists the tidy version of her story. She demands patience, nuance, and a better kind of looking.

I return to this world, again and again, because it isn’t only aesthetic to me. It’s a lens. A language. A way of learning to see women, art, and myself with more honesty than the myths allow.