“In the middle of the journey of our life, I found myself in a dark wood, for the straight path was lost.”

So begins Dante Alighieri’s descent into the afterlife, a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise that forms the epic Divine Comedy. These famous opening lines mark not just Dante’s pilgrimage, but in many ways, our own.

My own journey to Dante began not with his writing, but through art, specifically, the Pre-Raphaelites. It was the relationship between Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal that first drew me in. Siddal, his muse and wife, is often likened to Dante Alighieri’s Beatrice, and Rossetti painted her as such on more than one occasion. Beatrice, Dante’s muse and unattainable love, famously serves as his spiritual guide in The Divine Comedy.

Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix sparked a deeper interest for me. Painted after Siddal’s tragic death from a laudanum overdose in 1862, the work is a haunting tribute. Rossetti had created studies of her as Beatrice long before her death and returned to those sketches to complete the painting. In it, we see a transcendent Beatrice at the moment of death, with Dante and the figure of Love in the background. A dove delivers a poppy, one of the sources of laudanum, into her hand.

Beata Beatrix blurs the line between Elizabeth Siddal and Beatrice Portinari, turning Siddal into an eternal muse. Just as Dante immortalized Beatrice in his poetry, Rossetti immortalized Lizzie in his art… his own lost love, now imagined in paradise. The exhumation of Siddal’s grave to retrieve Rossetti’s buried poems only adds to the mythos and melancholy surrounding her legacy.

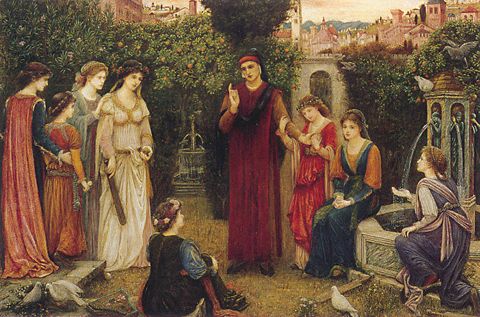

The Rossetti family’s deep engagement with Dante wasn’t accidental. Their father, Gabriele Rossetti, was a Dantean scholar, and his influence permeated their creative lives. Dante’s presence can be found in the works of many Victorian artists, but I’m especially fond of the Dante-themed paintings of Marie Spartali Stillman.

Before I began reading Dante’s own work in earnest, I realized I’d absorbed him mostly secondhand, through visual art and literary references scattered throughout popular culture. His shadow is long. We’ve all heard ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’ I first encountered Dante as a child, watching the 1946 Merrie Melodies cartoon Book Revue, where the villain falls into the Inferno. I was captivated by the idea of books coming to life, and by extension, by Dante’s fiery vision of the underworld.

Dante’s influence spans centuries. T.S. Eliot wove him into poetry. Lemony Snicket gave his narrator a lost love named Beatrice. Philip Pullman draws from Dante’s hell in The Amber Spyglass, and The Dante Club by Matthew Pearl turns the Commedia into the framework for a literary murder mystery. Dante’s vision of the afterlife has become our cultural blueprint for imagining Hell.

Last June, I picked up Reading Dante by Prue Shaw, hoping to engage more deeply with the Commedia. It offers rich context: Florentine politics, language, numerology, and brings Dante into the modern day. Far from being dry, Shaw’s work is both intelligent and accessible. I’ll return to it again. It’s helped elevate my appreciation for Dante to new levels.

Although I only read La Vita Nuova and The Divine Comedy for the first time two years ago, I was surprised by how much I enjoyed them. Dante’s reputation can be intimidating, but the experience of reading him felt familiar. His imagery, like Shakespeare’s, has soaked into our collective consciousness.

Watching Professor Giuseppe Mazzotta’s lectures on Dante was an invaluable supplement while reading Dante’s works. His passion is infectious, and his insights helped illuminate the journey.

Ultimately, The Divine Comedy is about two fundamental things: journeys and stories.

The journey, the symbolic movement from confusion to clarity, from darkness to light, is one we all undertake. And the stories heard in the voices Dante meets along the way, are what make his work endure. He doesn’t moralize or lecture; he lets his characters speak, and we, the readers, draw meaning from their words.

That’s why The Divine Comedy still resonates. It holds up a mirror to our own lives. Like Dante, we all encounter our own ‘dark wood,’ unsure of which path to take. Yet we move forward, becoming both characters and narrators in the stories of others. Hopefully, like Dante, we too will ‘come forth, and once again behold the stars.’

Dante’s epic remains a masterwork of beauty and introspection. It reminds us that poetic truths often carry more weight than literal ones. When life feels overwhelming, it’s this kind of truth that sustains us.

There’s a quiet comfort in seeing Dante’s influence ripple through generations of art and literature. Each era finds its own reflection in his words. Ars longa, vita brevis (art is long, life is short) and Dante’s art, thankfully, still speaks.

For more beauty, color, and curiosity, subscribe to the Guggums newsletter

Leave a Reply