Somewhere along the way, we learned a suspicious equation:

beauty = avoidance

joy = ignorance

aesthetic pleasure = moral failure

Art history disagrees.

The creation of art has rarely been a lounge chair on a sunny terrace. More often, it’s been a hand pressed to the wall in a burning building, testing for heat, searching for the exit, steadying the trembling. People have turned to images in plague years, war years, famine years, and exile years. Not because they were indifferent, but because the human psyche cannot metabolize catastrophe in a single sitting.

We do not live on truth alone. We live on truth with a pulse.

Beauty, then, isn’t a sugar coating.

It’s a nutrient.

It’s one of the ways we remain human while the world tries, daily, to render us numb.

Beauty as companionship, not denial

Behold: the modern feed, a corridor of sirens and screams. The news arrives like a tumultuous weather system. Uninvited, invasive, changing the pressure in the room. Many of us are walking around with a body that thinks it’s still in emergency mode: shoulders near the ears, jaw locked like a stubborn gate, breath held as if air must be rationed.

And then someone posts a painting. A small still life. A luminous face. A forest green drapery, a gold-edged sleeve. The comments split into two camps: How can you post this now? versus Thank you, I needed this.

I’m realizing that this is where Guggums lives: in the tender seam between those reactions. Not to arbitrate who is correct, but to ask a more useful question:

What if beauty isn’t a detour from reality, but a way to stay with it?

What if art, at its best, is not denial?

Perhaps it is companionship.

Community care isn’t always a grand sweeping movement. Sometimes it’s a “quiet room.”

When people say “community care,” we often imagine action: fundraising, organizing, showing up, building the infrastructure of survival. Yes. Absolutely. No argument from me; bring the banners, bring the water, bring the phone chargers.

But community care also includes something subtler: regulation.

A community of dysregulated nervous systems cannot sustain long-term work. If your body is constantly braced for impact, even your compassion will start to feel like a task you’re failing.

This is why we should make space for art.

Not art that says, “Everything is fine.”

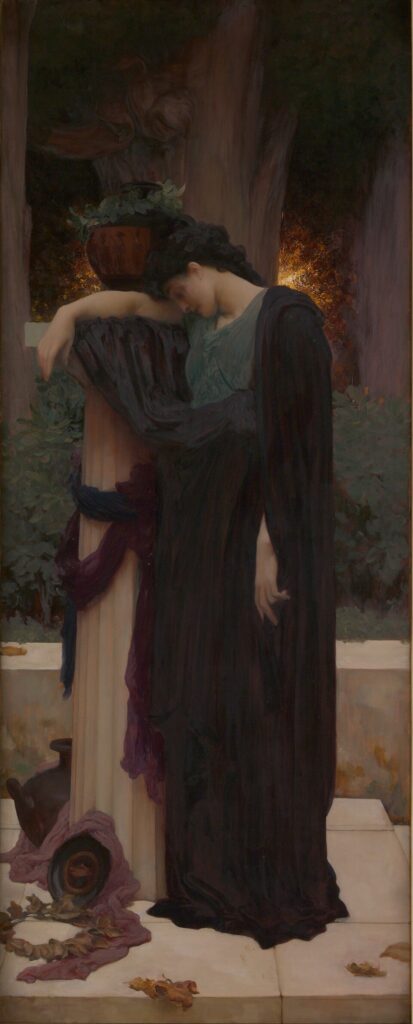

Art that says, “You are here. I am here. Breathe with me.”

Companionship, not denial.

What the painters knew: the eye can be a lifeline

Let us wander back through a few centuries, as one does.

The medieval icon: a stare that holds you steady

Icons aren’t “pretty.” They are present. Their gold grounds do not mimic the world; they insist that another kind of reality is available, one where your suffering is seen without spectacle. The gaze is frontal, unwavering. Not entertainment. Not escape.

A companion.

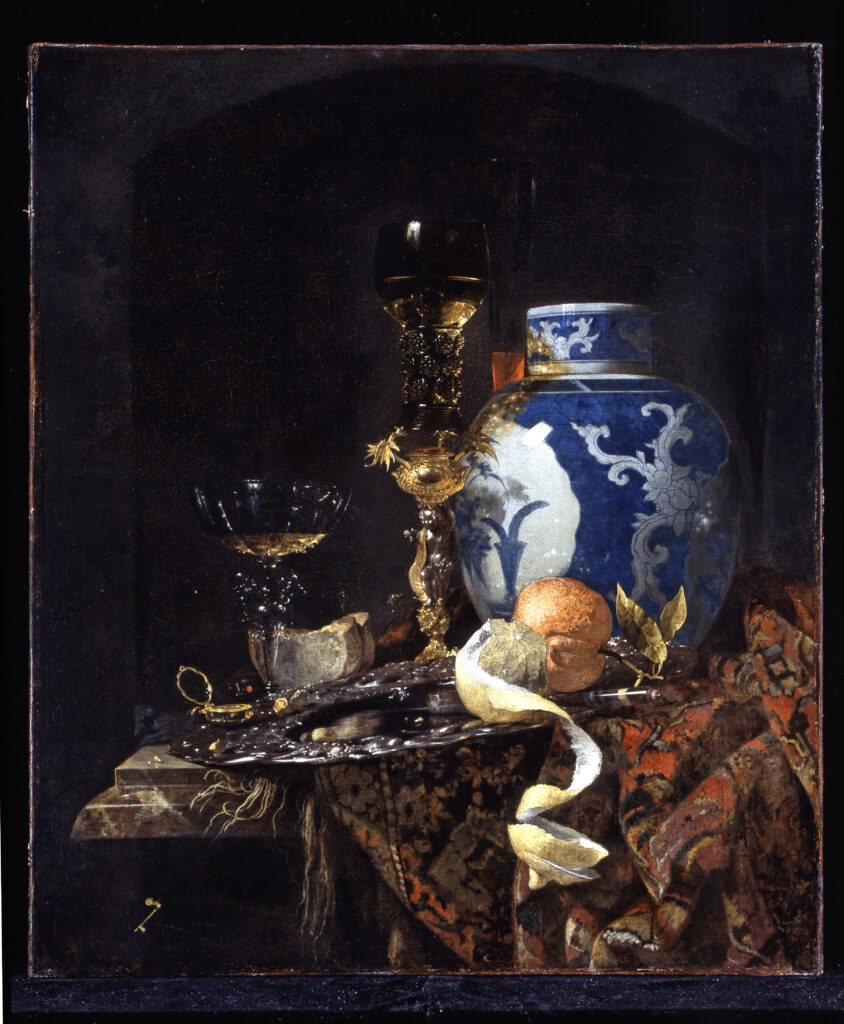

The Dutch still life: attention as resistance

A lemon peel spirals. A wineglass catches light. The tablecloth wrinkles like a small landscape. In eras shadowed by death (and yes, the Dutch knew plague and war intimately), still lifes were not naive. They were meditations on time, fragility, and the holiness of the ordinary.

Sometimes the most radical thing you can do is look slowly.

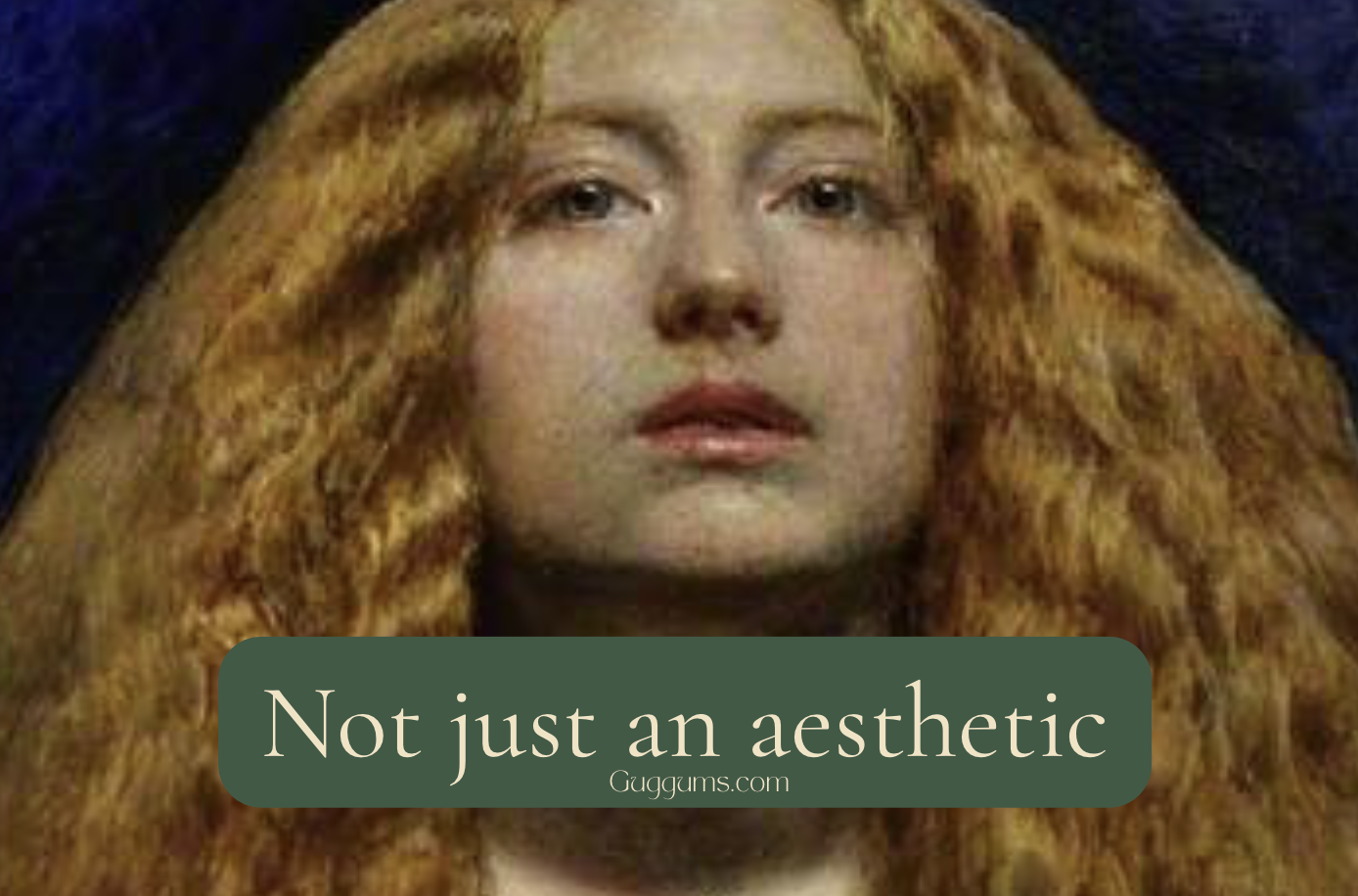

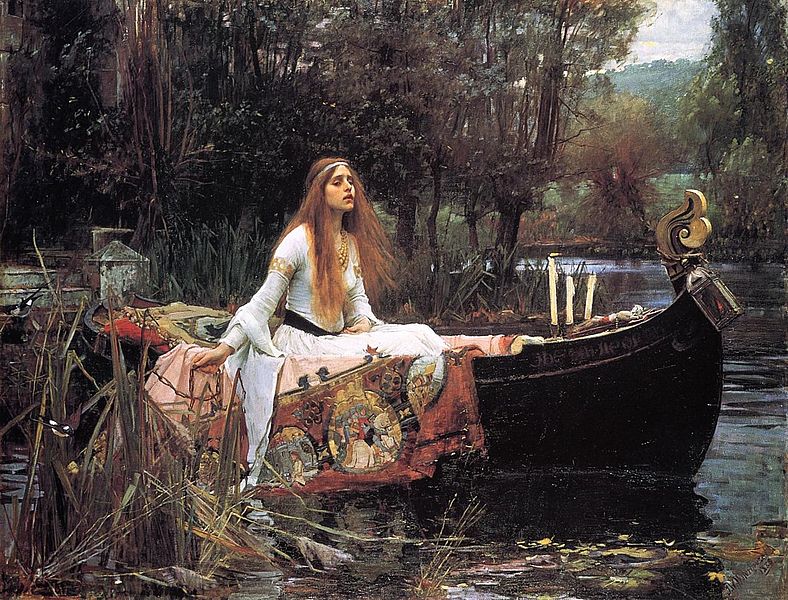

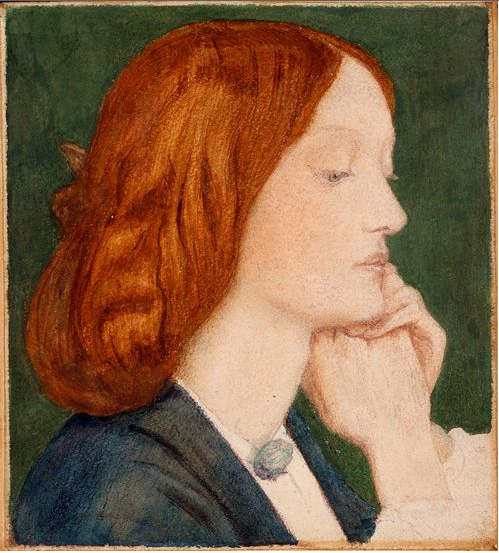

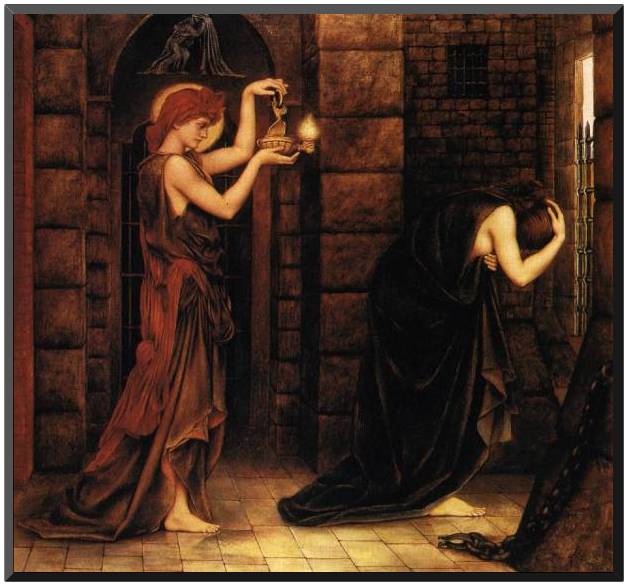

The Pre-Raphaelite dream: beauty with a bruise

Those lush greens and medieval reveries? They weren’t just aesthetic indulgence. They were a protest against industrial brutality, against a world flattening into soot and speed. Their beauty wasn’t complacent; it was insistent.

Art doesn’t always solve. It often stays.

The difference between tone deaf and tender

So how do we share beauty without sounding like we’re handing someone a lavender-scented bandage for a broken bone?

Here’s the difference, distilled:

Tone deaf beauty says: “Look at this and stop feeling bad.”

Tender beauty says: “Look at this while you feel what you feel.”

Tone deaf beauty insists on a pivot.

Tender beauty offers a parallel lane.

Tone deaf beauty performs positivity.

Tender beauty practices presence.

Tone deaf beauty centers the poster’s comfort (“let’s keep it light!”).

Tender beauty centers the audience’s reality (“this is heavy; you’re not alone”).

If you want a rule you can carry in your pocket like a coin:

Do not use beauty to erase pain. Use beauty to accompany people who are in pain.