This is where The Tempest slips off the page. Pre-Raphaelite attention pins unseen magic to a real patch of grass and leaf, until the atmosphere around him feels nearly touchable.

A quick Tempest refresher (no homework required)

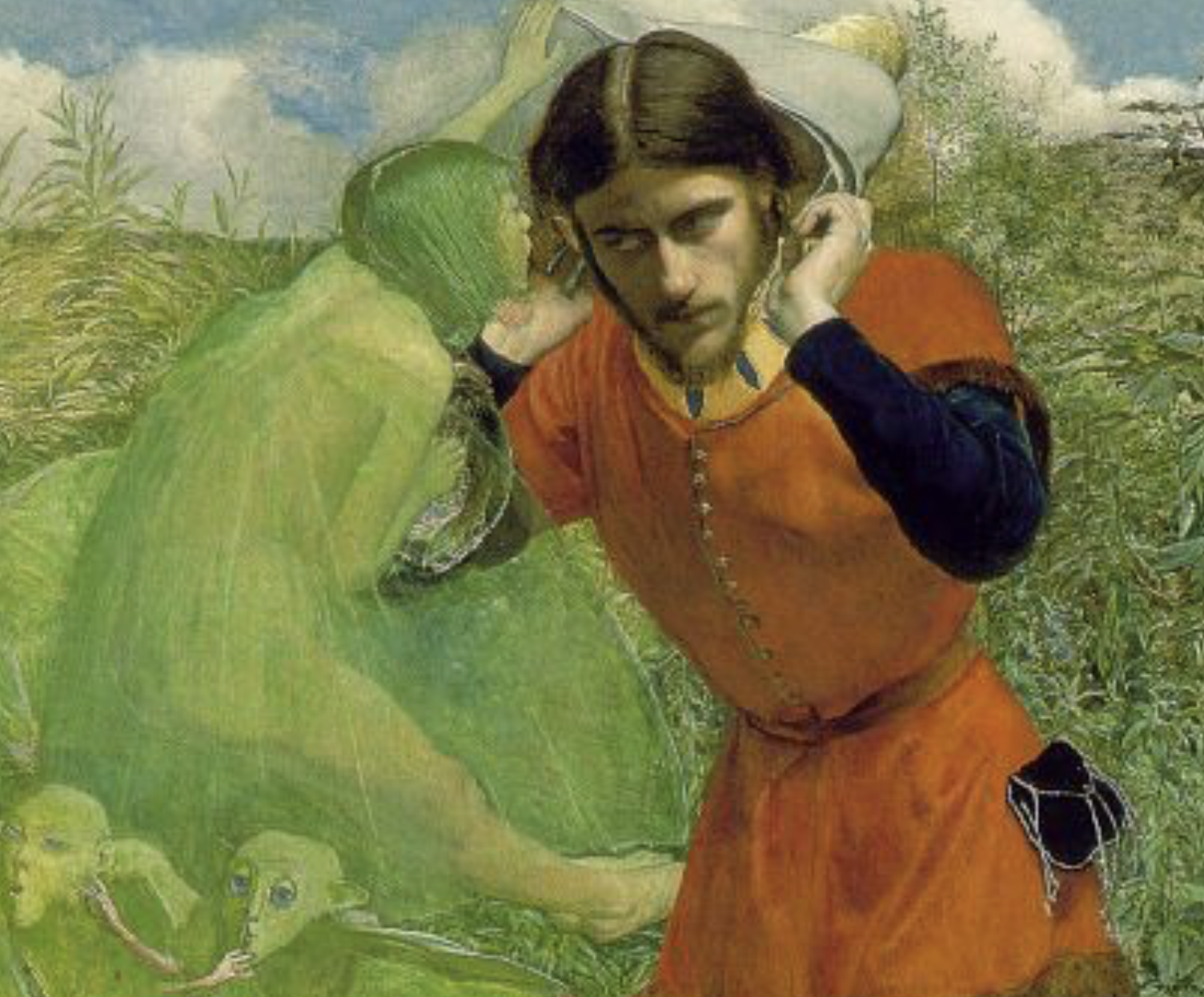

Millais is painting an episode from The Tempest, Act I, Scene II: Ferdinand, shipwrecked on Prospero’s enchanted island, hears music and tries to locate it “i’ the air or the earth?” as Ariel sings “Full fathom five thy father lies.”

This is the moment where the island begins to do what it does best: guide you without asking permission.

What’s happening in the painting

Ferdinand is foregrounded and intensely physical, wearing a red tunic, white hose, with one foot edging forward; yet his face is turned inward, listening. Ariel is there, but not there: a green, surreal presence tipping Ferdinand’s hat, close enough to touch him, impossible to truly see.

And then there are the wonderfully odd little creatures, green “bats” posed in a way that echoes “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil,” a detail that reportedly unsettled at least one early would-be buyer because it wasn’t the sweet, dainty fairy world people expected.

Millais isn’t offering a Victorian stage fairy. He’s giving you something stranger: nature itself behaving like theatre.

Why this painting matters in Pre-Raphaelite terms

This work is often pointed to as Millais’ first big attempt at the early PRB “paint what you actually see” intensity, done outdoors (plein air) at Shotover Park near Oxford.

That shows in the greenery. The plants aren’t “background.” They are presence: each clump, blade, and leaf treated as if it has rights. (This is the Pre-Raphaelite promise: the world is not a blur behind the story; the world is part of the story.)

There’s also the PRB brightness. Millais painting with heightened, saturated color, including working on a white ground to keep the whole surface lit from beneath. The red tunic against that ferocious green is basically a visual bell: you can almost hear it.

The genius choice: making the invisible visible (without ruining it)

How do you paint a spirit like Ariel, without making them into a literal cartoon fairy?

Millais’ solution is sly: he lets Ariel half disappear into the green, more like camouflage than costume. Ferdinand looks right at him, and still can’t see him. We, the viewers, can (sort of.)

It’s a perfect visual equivalent of the scene: Ferdinand is being led by something he can’t name. The island doesn’t announce itself. It insinuates.

A few things to notice when you look

- The hands at Ferdinand’s ears: he’s not just hearing, he’s straining, trying to catch meaning.

- That hat string detail: such a small, domestic tether in a supernatural moment, and it makes the enchantment feel practical.

- The arched/circular framing: it reads like a portal, a vignette, a “peep into another world” shape. Very fairy tale, but also very controlled.

- The greens: not one green, but many: acid, moss, olive, yellow green, stacked until “nature” becomes almost hallucinatory.

A tiny afterlife note (because art has one)

The finished painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1850, and it has lived largely in private collections; it even became the subject of a UK temporary export bar in 2019, a reminder that these early PRB works are still treated as cultural treasures with real stakes attached.

Why I keep coming back to it

Because it’s not just “Shakespeare, illustrated.”

It’s Shakespeare filtered through that Pre-Raphaelite conviction that the world is charged, that grass and shadow can be as dramatic as a human face; that beauty can be exacting, almost severe; that the supernatural doesn’t have to glitter to be real.

Millais shows us a man lured by a musical spell.

And if you’ve ever felt art do that to you, pull you forward by the collar with something you can’t quite explain, then you already know this painting’s secret.

For more beauty, color, and curiosity, subscribe to the Guggums newsletter