Introducing kids to Victorian art isn’t about lectures or timelines; it’s about opening a window into a world where stories glow in color, details brim with meaning, and imagination runs gloriously wild.

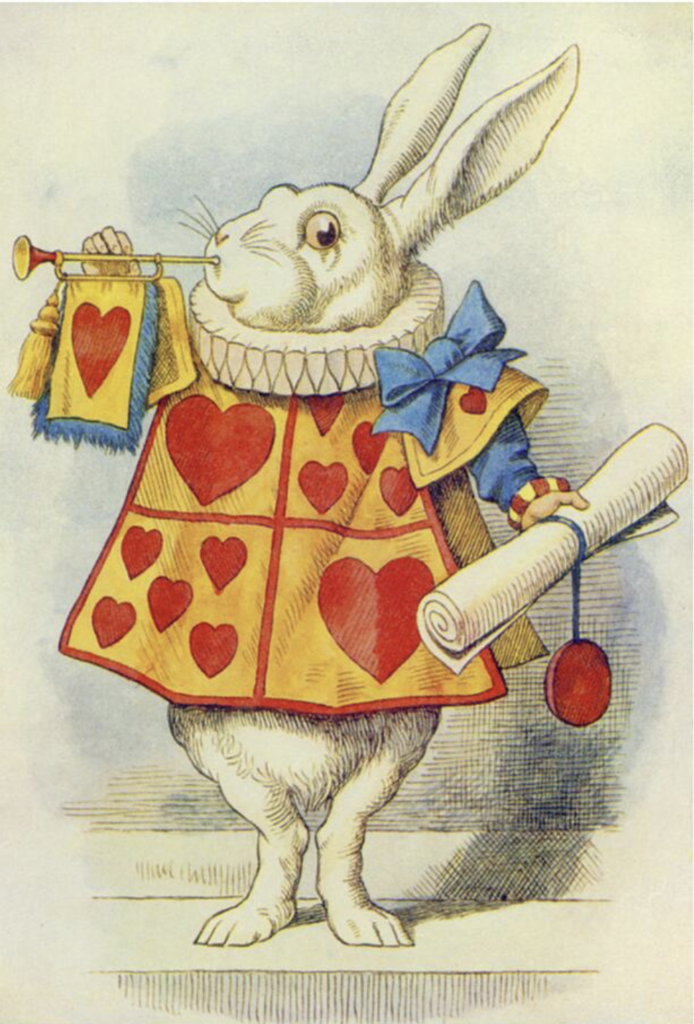

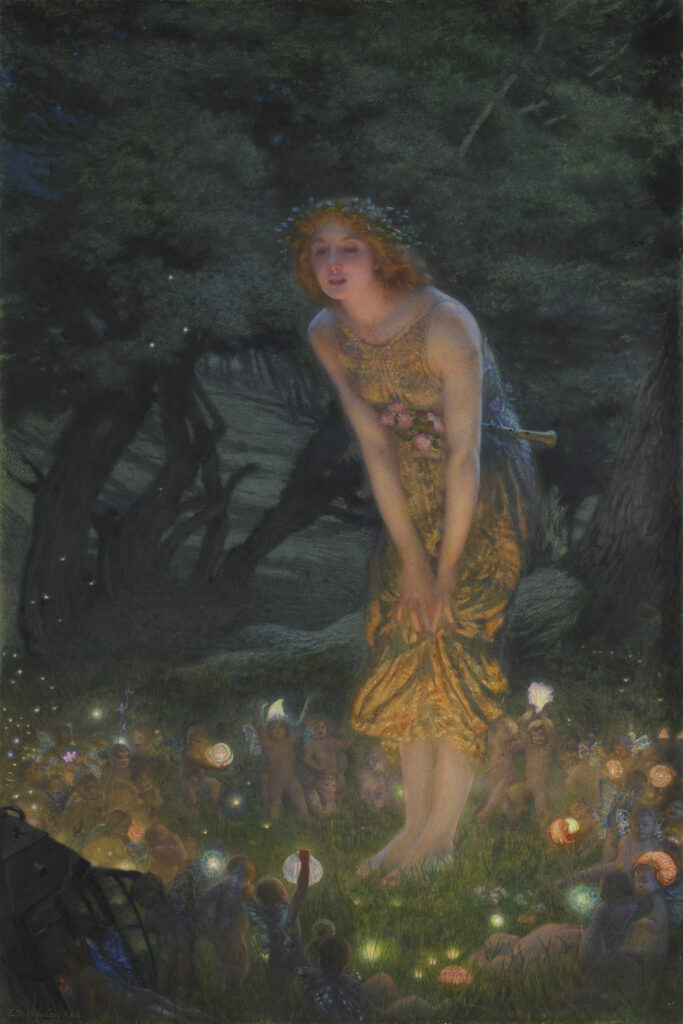

Ultimately, Victorian art, especially the works of the Pre-Raphaelites, offers exactly the kind of visual richness children instinctively respond to. It’s theatrical and emotional. Art of the 19th Century is filled with hidden objects, dramatic gestures, fairy tale settings, animals, flowers, myths, and expressive faces. In other words: it’s perfect for kids.

Here are a few ways to share the magic with them.

Start With the Stories

Victorian art is steeped in storytelling. There’s no need to begin with technical art terms. Start with the narrative.

Ask questions like:

- “What do you think is happening here?”

- “Who do you think this person is?”

- “What do you see first?”

- “What would happen next if this painting were a book?”

Works like Millais’ Ophelia, Rossetti’s The Day-Dream, Holman Hunt’s The Lady of Shalott, and Waterhouse’s The Soul of the Rose are just a few examples of works that instantly invite storytelling. Children naturally fill in the gaps.

Victorian painters adored literature and tales of fairy tales, medieval romances, Shakespeare, Tennyson. Children adore stories, too. This is your bridge.

Notice the Details (Victorian Artists Loved Them)

Victorian artists painted like detectives: every blossom, book, feather, gesture, and ray of light meant something.

Encourage your kids to:

- Describe any jewelry or interesting items, such as furniture

- Spot animals, insects, or flowers

- Count objects

- Search for symbols

- Notice clothing or expression changes

Turn a painting into a treasure hunt. Suddenly, Victorian art becomes interactive rather than dusty.

Connect Art to Nature

The Victorians, especially the Pre-Raphaelites, were obsessed with nature. They painted outdoors, studied plants, and described leaves and flowers with botanical accuracy.

Bring art into the physical world:

- Go on a nature walk and find leaves that match the paintings

- Bring a book of flowers and identify what’s in Ophelia’s hands

- Compare real petals to Waterhouse’s roses

- Sketch outside like Millais or Rossetti

- Collect and press flowers in a book

Art becomes less like a museum label and more like a living, breathing world they can step into.

Encourage Them to Make Their Own Victorian Inspired Art

Children should experience the art in their hands, not just their eyes.

Ideas:

- Paint or draw using muted Victorian palettes (moss green, rose, gold, sky blue)

- Create a portrait of a favorite toy “Victorian style”

- Illustrate their own myth or fairy tale

- Make a paper crown for a Pre-Raphaelite hero or heroine

- Try watercolors to capture “dreamy” soft light

- Copy a tiny corner of a larger painting

Art becomes play… and play becomes understanding.

Use Children’s Books and Kid-Friendly Resources

Victorian art pairs beautifully with:

- Illustrated storybooks

- Mythology or fairy-tale collections

- Short bios of artists

- Kid-friendly museum guides

- Graphic novel versions of classics

If your child enjoys Greek myths or fairy tales, Victorian art’s interpretations of those stories will feel like natural extensions.

Visit a Museum (or Create a “Home Museum”)

Children thrive when art is an experience

At a museum:

- Visit one or two Victorian paintings, not twenty

- Spend time with a single artwork and talk about it

- Encourage them to find “their favorite detail”

- Bring a notebook and let them sketch quietly

At home:

- Print a few paintings and hang them at kid-eye level. Or use postcards; there are so many gorgeous postcards of paintings available online.

- Make a rotating “gallery wall”

- Have a weekly “choose a painting” ritual

- Use the prints as inspiration for bedtime stories. You can take turns making up your own stories about paintings, no doubt your children can thrill you with their own imaginative tales!

Victorian art becomes familiar, comforting, and part of the daily fabric of life.

Talk About Feelings, Not Facts

Children don’t need dates or movements, that can come later, if they want. Right now, they need connection.

Ask:

- “How does this picture make you feel?”

- “What do you think she’s thinking?”

- “Does this scene look calm? Sad? Exciting?”

- “Which character would you be?”

Victorian artists loved depicting emotions such as longing, courage, frustration, hope, curiosity, enchantment. Children instinctively read these expressions and respond with honesty.

Let the Art Be a Conversation Starter

Victorian art opens gentle doors to big topics:

- Why do people tell stories?

- Why do artists make things beautiful?

- What makes a hero?

- What is imagination?

- Why do we look at art at all?

Art is a safe, effective way of talking about life. Go for it!

Introducing your children to Victorian art isn’t about building mini art historians (unless that’s what they want!), it’s about giving them a set of eyes that notice beauty, pattern, emotion, and story. The Victorians believed art should enrich the spirit, awaken empathy, and spark the imagination and that’s a perfect recipe to capture your child’s wonder!

For more beauty, color, and curiosity, subscribe to the Guggums newsletter

Leave a Reply