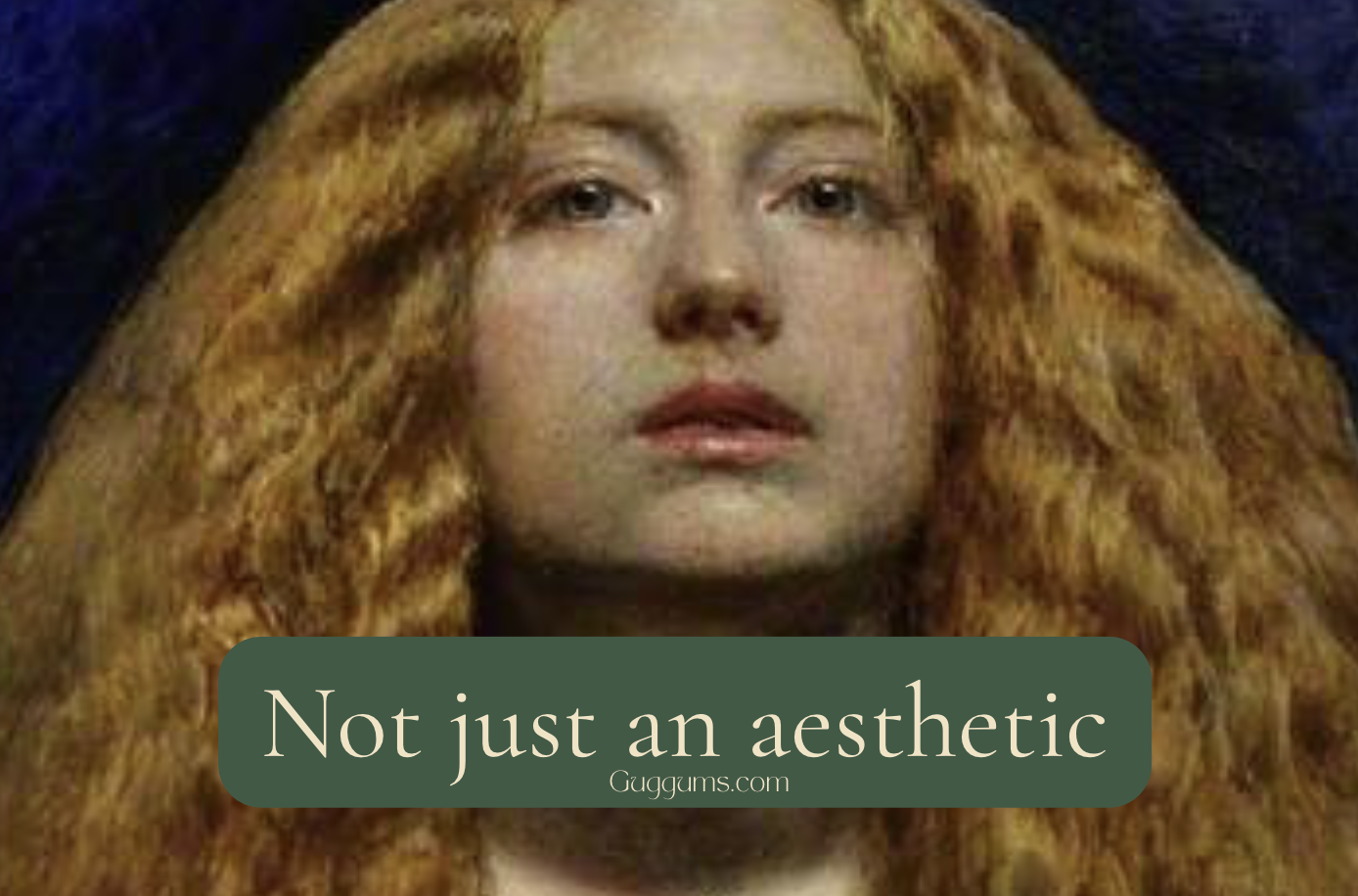

Somewhere along the way, “Pre-Raphaelite” became shorthand for a look: abundant hair, pale skin, some moody greenery. A woman who seems to have wandered out of a medieval daydream and into your Pinterest feed.

I understand the appeal, but when we reduce the Pre-Raphaelites to solely an aesthetic, or a vibe, we miss the thing that made their work so unnervingly alive.

The Pre-Raphaelites weren’t a hairstyle. They were a worldview.

They treated nature not as backdrop but as a living language. A river wasn’t scenery; it was fate. A flower wasn’t decoration; it was a message. The world itself seemed to press in with meaning.

And they treated stories the same way.

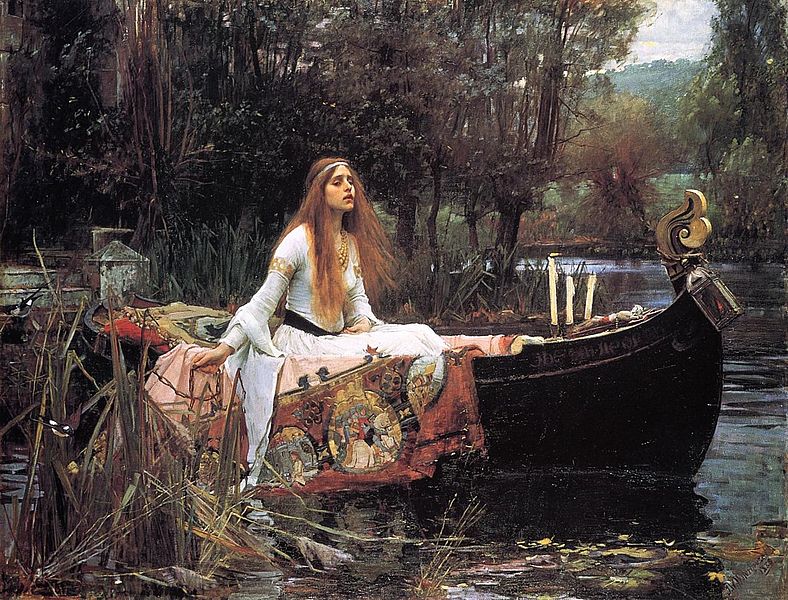

Myths, legends, Shakespeare, Arthurian romance… these weren’t merely escapism. They were serious material, charged with warnings and longings. Their paintings don’t merely “illustrate” a tale; they interrogate it. Who is being sanctified? Or being punished? Who is being turned into a symbol instead of allowed to be a person?

That last question matters more than ever, because the visual internet trades in symbols. A tragic girl. The beautiful woman framed as a mood, “Opheliacore,” the languid gaze, the hair like a halo. The Pre-Raphaelites gave us many of those visual templates.

They also, if we’re honest, helped build the cage: the idea that beauty is virtue, that suffering is poetic, that women look best when they are luminous and still.

Just look at Millais’ Ophelia, or Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott. Women suspended in a moment of aestheticized tragedy, turned into icons of doomed grace. (See Pre-Raphaelite Women at The Victorian Web and the Pre-Raphaelite Collection at The Tate.)

Which is why we shouldn’t throw the aesthetic away. We should wake it up.

If we love Pre-Raphaelite beauty (and of course we do!) we can love it with our eyes open, looking past the hair and ask what the painting is teaching you about desire, virtue, power, punishment, and the cost of being seen. Let the art be both gorgeous and complicated. Roses with thorns.

Because that’s the real inheritance.

Not the curls.

The way of seeing.

For more beauty, color, and curiosity, subscribe to the Guggums newsletter