by Stephanie Chatfield

“The mirror crack’d from side to side;

‘The curse is come upon me,’ cried

The Lady of Shalott.”

In Tennyson’s haunting poem, the Lady of Shalott lives in isolation, barred from engaging with the world. Instead, she weaves tapestries, catching only distorted glimpses of life through a mirror. Her reality is one of distance, watching, never participating.

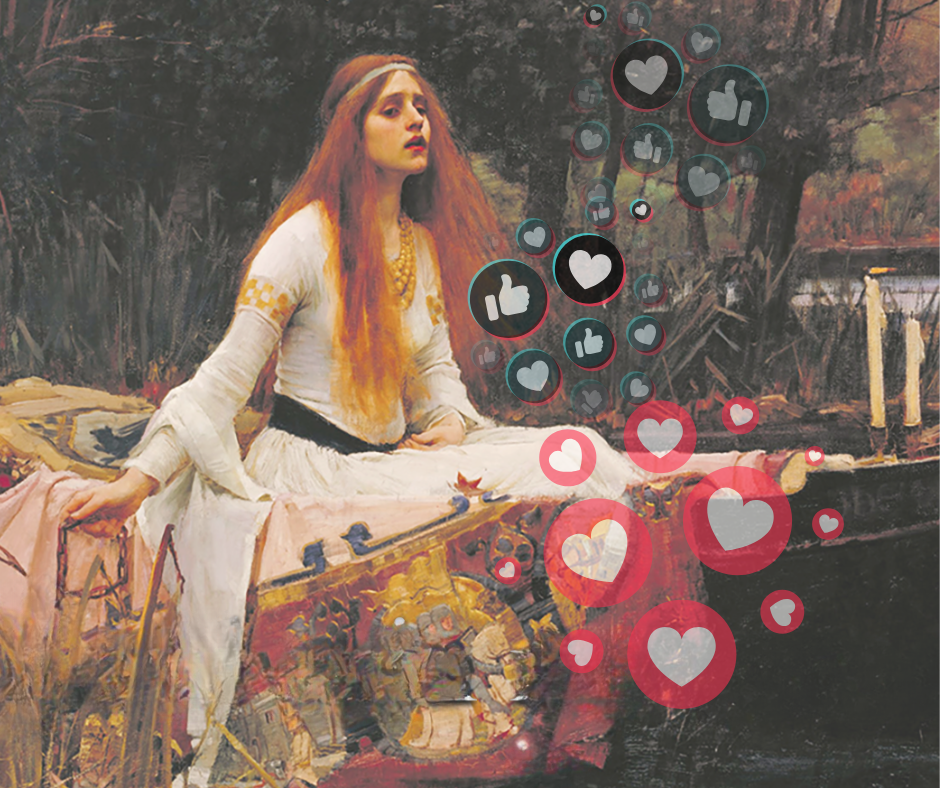

To 19th century readers and the Pre-Raphaelite artists the poem inspired, she may have represented the ideal of feminine passivity or artistic sacrifice. But from our 21st-century vantage point, the story hits differently, though perhaps not as differently as we’d like to believe.

Despite the progress we’ve made, modern women still contend with a kind of separation. We have separate labels for books by and for women (chick lit.) We often tag films directed by women as niche. Society describes aging men as ‘distinguished’, but discourage signs of it in women. These aren’t relics of the past; they’re present-day mirrors that reflect distorted values.

I recently read a thread criticizing The Lady of Shalott for being a passive figure, cursed to spend her life weaving. But that’s the point. Her fate is tragic. The poem wants you to feel her frustration, her entrapment.

So what do we do with her now? Should we dismiss her as just another outdated symbol? Or can we reclaim her?

The Lady’s mirror showed her phantoms; ours show idealized bodies, filtered lives, and curated perfection.

While the Lady remains passive, she lives. The moment she chooses autonomy, when she looks directly at the world, she dies.

Her death feels eerily familiar to many women: not always physical, but social. Choosing your own path can feel like a risk to your identity, reputation, or relationships.

And yet, even within her confinement, the Lady delights in her weaving. That resonates too. We all weave webs… Instagram grids, curated TikToks, filtered selfies. And just like her, we risk becoming trapped in our creations, consumed by likes, comparisons, and the pursuit of an unattainable ideal.

The Lady’s mirror is our screen. And maybe it’s time to crack it.

There’s strength in reclaiming the Lady of Shalott, not as a warning, but as a rallying cry. We can break our own mirrors. We can step outside, even if it means risking discomfort, even if someone doesn’t approve.

Tennyson may have been writing about women’s roles or the isolation of artists. Either way, his poem holds power.

Let it be a reminder: we don’t have to live in reflection. We can create, speak, and live on our own terms.

More Adventures

- A Pre-Raphaelite Look at Hitchcock’s Vertigo

- Balancing on the Bridge

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Home

- On Storms

- Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens

- Pre-Raphaelite Princess of Star Wars

- Seeing The Beatles through Paul McCartney’s Lens

- St. Pancras Old Church Gardens

- The Magic Down the Rabbit Hole

- The Wounded Dove

- Unconventional Beauty

- Visiting Lizzie Siddal at Highgate Cemetery

- Westminster Abbey

- What Grows from Grief