by Stephanie Chatfield

Dante Gabriel Rossetti — Victorian poet, painter, and a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood — grew up under the immense influence of Dante Alighieri. Though the medieval poet lived centuries earlier, Dante was a constant presence in the Rossetti household. Gabriel’s father, Professor Gabriele Rossetti, an Italian exile who moved to London in 1824, was convinced that Dante’s Vita Nuova and Divine Comedy contained hidden references to Freemasonry.

Gabriele Rossetti dedicated much of his life to uncovering and proving these supposed connections. Sadly, his interpretations were far-fetched and ultimately discredited. After his death, his widow, Frances, burned much of his unpublished work. For a deeper exploration of the Rossetti family and Gabriele’s Dantean obsession, I highly recommend Dinah Roe’s The Rossettis in Wonderland: A Victorian Family History.

When Professor Rossetti’s first son was born in 1828, he named him Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti — ‘Gabriel’ and ‘Dante’ for obvious reasons, and ‘Charles’ in honor of Charles Lyell, a fellow Dante enthusiast and the boy’s godfather. After Lyell’s death, the young Rossetti dropped ‘Charles’ and adopted the name Dante Gabriel Rossetti professionally. Among friends and family, however, he was always simply ‘Gabriel’.

Dante Alighieri was not just a name in Gabriel’s life — he was an unavoidable ghost. In his youth, Gabriel gravitated toward English writers like Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott, but Dante’s influence ultimately became ingrained in his work and spirit. Rossetti would later translate Dante’s Vita Nuova and find deep personal parallels between his own love for Elizabeth Siddal and Dante’s devotion to Beatrice — immortalized in both La Vita Nuova and The Divine Comedy.

Dante Alighieri first encountered Beatrice when they were both nine years old, and he later wrote of this moment in Vita Nuova: “Behold, a deity stronger than I; who coming, shall rule over me.” Dante loved Beatrice from afar until her untimely death at 24 in 1290.

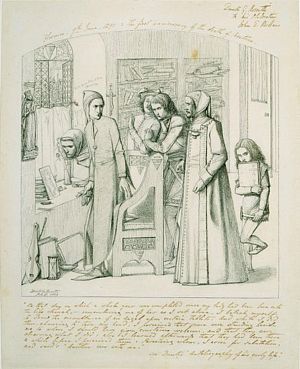

Gabriel’s fascination with Dante extended into his artwork. One particularly compelling piece is his drawing of Dante, inspired by Seymour Kirkup’s copy of a lost Giotto portrait of the poet. Kirkup, a close friend of Professor Rossetti, had located the faded fresco in Florence and made a tracing and painting of it before its destruction during restoration. Gabriel later painted Giotto Painting Dante, depicting Giotto at work while Dante gazes longingly at Beatrice. Also featured in the scene are Cimabue, looking over Giotto’s shoulder, and Guido Cavalcanti, standing to Dante’s left.

Rossetti also illustrated passages from Vita Nuova in his 1855 watercolor Beatrice Meeting Dante at a Marriage Feast. Here, Elizabeth Siddal’s features are unmistakably used for Beatrice.

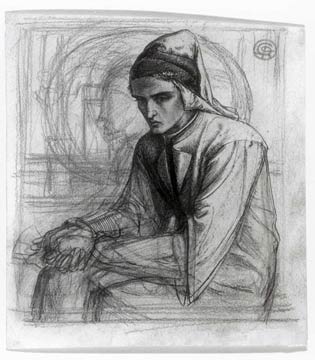

Siddal, discovered while working in a millinery shop, first posed for artist Walter Deverell before becoming Rossetti’s exclusive model, pupil, muse—and eventually, wife. Rossetti once confessed to Ford Madox Brown that he felt his destiny was sealed upon meeting Lizzie. His idealization of her mirrored Dante’s idealization of Beatrice.

Siddal’s presence permeates many of Rossetti’s Dantean works. She appears in Dante’s Vision of Rachel and Leah and as Francesca da Rimini from The Divine Comedy. In Canto V, Dante encounters the ill-fated lovers Francesca and Paolo in the second circle of Hell, punished for their adulterous affair. Rossetti painted this scene in haste to sell the work to John Ruskin, using the proceeds to join Siddal in Paris during a time of financial hardship.

Bird imagery, significant in Dante’s Divine Comedy, also found its way into Rossetti’s descriptions of Siddal. Dante writes of lovers drawn together like doves, and Rossetti frequently referred to Lizzie as a dove in his poems and letters—calling her “dear dove divine” and even using a dove symbol to represent her in correspondence with his brother. Whether consciously or subconsciously, Rossetti echoed Dante’s imagery in his own relationship.

The tragic themes of love and death also shaped Rossetti’s poetry. Inspired by both Dante and Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven, he wrote The Blessed Damozel, a meditation on love after death. This motif became painfully personal after Siddal’s death from a laudanum overdose. In works like Beata Beatrix, Rossetti memorialized her as a Beatrice-like figure—unreachable in the afterlife but eternally enshrined in art.

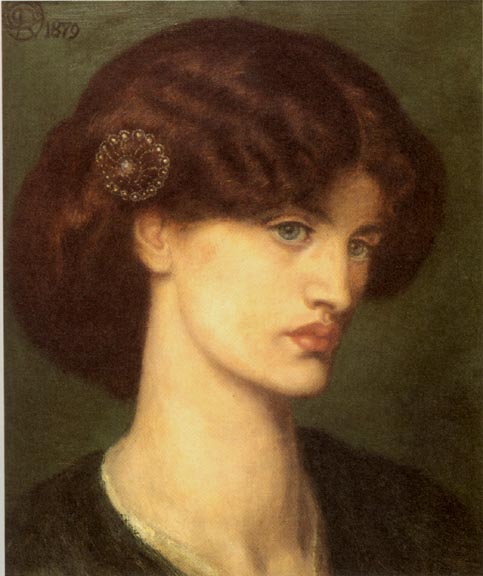

Later, Jane Morris, wife of William Morris, became another of Rossetti’s muses. She too was cast in Dantean roles, appearing as Pia de’ Tolomei from Purgatorio in La Pia de Tolomei. In Rossetti’s largest Dantean canvas, Dante’s Dream, he depicted Dante dreaming of Beatrice’s death. Poppies litter the floor, symbolizing death and sleep, while Jane Morris appears as Beatrice, though Rossetti gave her the red hair once associated with Siddal.

Dante remained a constant thread throughout Rossetti’s life. Although first inspired by his father’s obsessive scholarship, Rossetti made Dante’s world uniquely his own—through translations, paintings, and poetry that bridged centuries of artistic devotion.

“In that book which is my memory,

On the first page of the chapter that is the day when I first met you,

Appear the words, ‘Here begins a new life.’” — Dante Alighieri, Vita Nuova

More about the Pre-Raphaelites

- Birth of the Brotherhood

- John Everett Millais: The Prodigy Who Painted Emotion

- Pre-Raphaelite FAQs

- Pre-Raphaelite List of Immortals

- Pre-Raphaelite Luminosity

- Pre-Raphaelite Women

- The Diaries of William Allingham

- What is the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Woman?’

- William Holman Hunt: The Visionary of Pre-Raphaelite Symbolism