by Stephanie Chatfield

If you’re serious about studying the Victorian era, diaries and letters are essential. Sometimes I feel like a 21st-century eavesdropper, eagerly devouring personal journals and private correspondence whenever I can.

Through these firsthand accounts, the past doesn’t always spring vividly to life, but it does pierce the mist with greater clarity.

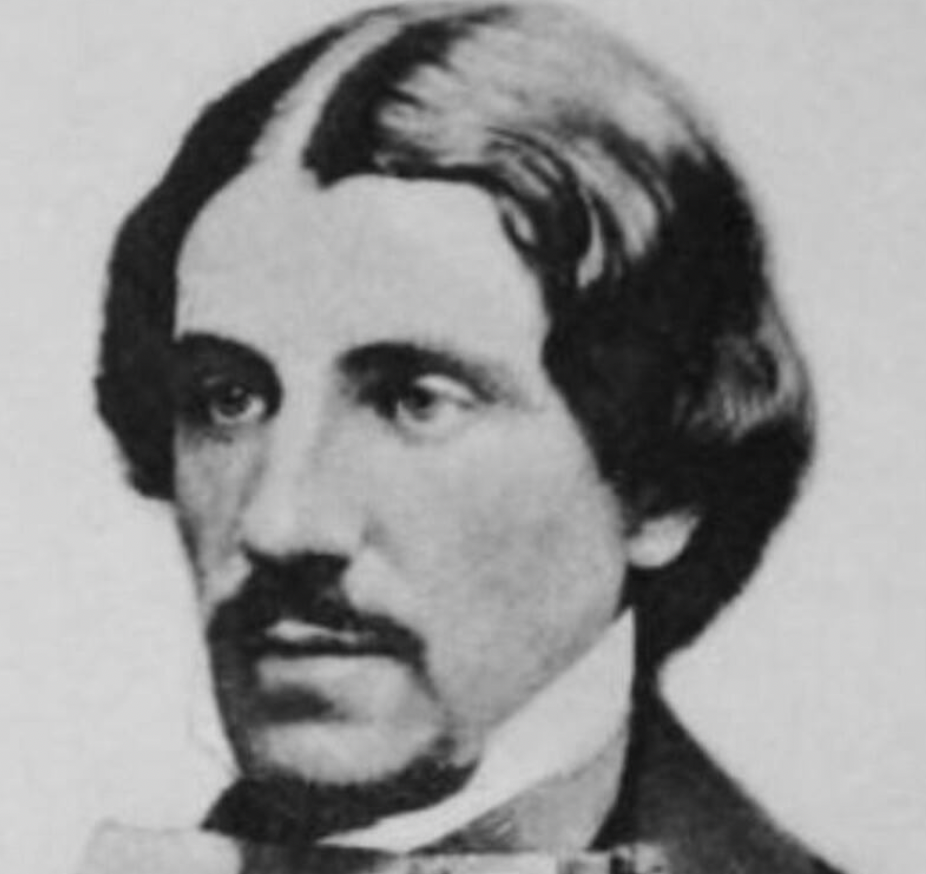

The diaries of Irish poet William Allingham are a perfect example of this subtle magic.

A true lover of the written word, Allingham sought out friendships with many of the 19th century’s most creative minds. His diary offers a rare, intimate glimpse into the lives of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Tennyson, Julia Margaret Cameron, and others.

Covering the years from 1824 to 1889, his firsthand account is both captivating and invaluable. While his longer passages draw you in with their richness, it’s often the briefest entries that are the most poignant: “28 October: Evening. Moonlight. Molière.”

Allingham was an avid reader, and the frequent references to books throughout his diaries are of particular interest to me. I’ve compiled a list of the titles he mentions and added it to the end of this post.

A Glimpse into the Pre-Raphaelites

I first became interested in Allingham’s diaries when I launched LizzieSiddal.com, a website dedicated to the Pre-Raphaelite model and painter Elizabeth Siddal. Siddal was one of the earliest faces of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, immortalized as Millais’ drowned Ophelia and muse to Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whom she later married.

In some versions of Siddal’s discovery by the Brotherhood, it was Allingham who introduced her to the young artists. Smitten with one of her co-workers, he supposedly mentioned her to Walter Deverell when Deverell was searching for a model for his painting Twelfth Night.

Other accounts, including William Holman Hunt’s Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, claim that Deverell discovered her himself while visiting the millinery shop with his mother.

Curious to confirm the story, I turned to Allingham’s diary, only to be disappointed. Although he mentions both Siddal and Rossetti, there’s no suggestion that he played a role in their introduction. Does that mean the story is untrue? I can’t confirm it, but neither can I dismiss it outright. It remains unsubstantiated, and after all, Allingham never documents meeting or courting his own wife either. Helen Allingham, an artist in her own right, simply appears in the diaries after their marriage.

It seems that both accounts of Siddal’s discovery have come to us through hearsay. The version involving Allingham can be traced to Violet Hunt’s 1932 book Wife of Rossetti, where, according to Jan Marsh in Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, Hunt claimed to have heard the story from Allingham’s widow after the poet’s death. The Deverell version comes from Holman Hunt’s own memoir. Most likely, the truth lies somewhere between the two. (I can’t resist adding that Violet Hunt’s biography is far from reliable! It’s gossipy, full of unverified anecdotes, and prone to imaginative flourishes. If you’re only going to read one book about Siddal, let it not be that one.)

I didn’t find the answer to my original question in Allingham’s diaries, but I found something far richer.

With a keen and careful eye, he captures the men of letters he so admired, noting even the smallest details.

Slices of Life

But he doesn’t limit himself to the literary elite. He also records glimpses of the less fortunate…like a young girl sentenced to seven years’ transportation for stealing a purse: “She is removed shrieking violently. It seems a severe sentence.” Or his visit to a poorhouse, where he meets Tom Read, “a crazy man with small sharp black eyes; sometimes keeps a piece of iron on his head to do his brain good; plays on a fiddle, the first and second strings only packthread.”Allingham promises to bring him proper violin strings.

What he chose to record reflects his deep love of literature and his enduring admiration for writers. He didn’t seem interested in meticulously documenting every conversation, only the ones that struck him, the ones he wanted to preserve. Even when he disagreed, he presented his friends’ differing opinions with respect. His physical descriptions are vivid and memorable too: “Ouida (Louise de la Ramee) in green silk, sinister clever face, hair down, small hands and feet, voice like a carving knife.” Or his sharp portrait of Nathaniel Hawthorne: “features elegant though American.”

An Eye for Detail

In 1849, just a year after the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Allingham made the acquaintance of Coventry Patmore. During a visit to Patmore’s home, he noticed a cast of a statuette by the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner. What stands out is the level of detail in Allingham’s account, not just of the sculpture itself, but of every aspect of the visit. Throughout his journals, Allingham captures the great writers he meets within their own surroundings, carefully describing their homes, the conversations they share, and even the books he happens to spot on their tables. It’s this attention to minutiae that makes his diaries so captivating.

Two small sitting-rooms with folding door between: front room has engraved portraits of Wordsworth and Faraday over the mantelpiece (‘the two greatest men of our time’), a round table with ten or a dozen books, and plaster cast of statuette of Puck — just alighted on a mushroom and about to push with his toe a bewildered frog which a snake is on the point of snapping up. You can see that he saves the frog out of fun mostly, and to tease the snake. He is a sturdy elf, plainly, yet not humanly, masculine. A very original bit of work, by ‘a young artist named Woolner’. In the back room P’s writing-table at the window, with a few bookshelves beside it. I notice Coleridge’s ‘Table Talk‘ and ‘Aids to Reflection’, and Keats’s ‘Remains’. Them we started on a walk northward. Patmore thoroughly agrees with me that artistic form is necessary to poetry.

A visit to Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1864 gives us a now-famous glimpse of the model Fanny Cornforth, whose dialect made her the subject of amusement, no doubt to her embarrassment.

“Down to Chelsea and find D.G. Rossetti painting Venus Verticorida. I stay for dinner and we talk about the old P.R.Bs. Enter Fanny, who says something about W.B. Scott which amuses us. Scott was a dark hairy man, but after an illness has reappeared quite bald. Fanny exclaimed, “O my, Mr Scott is changed! He ain’t got a hye-brow or a hye-lash — not a ‘air on his ‘ead!’ Rossetti laughed immoderately at this, so that poor Fanny, good-humoured as she is, pouted at last–“Well, I know I don’t say it right,” and I hushed him up.”

He visits the Red House to see William Morris and his “queenly wife crowned with her own black hair.” Allingham describes Morris with clear affection: “I like Morris very much. He is plain-spoken and emphatic, often boisterously, without an atom of irritating manner.” On a visit to Edward Burne-Jones’ studio, Allingham offers a vivid glimpse of works in progress: “Saturday, 28 October. 41 Kensington Square — two studios. ‘Zephyr carrying Psyche’ — delightful — precipice, green valley, Love’s curly little castle below. Designs of ‘St. George and Dragon.’ Drawings of Heads. Circe (a-doing), she stretching her arm across.”

Two accounts of the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron are quite humorous. In the first, Tennyson is clearly teasing her, while in the second, we catch a glimpse of the great poet’s reaction to JMC’s photograph of him, as well as her exasperation with those who refuse to be photographed.

Right: Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron

(November 1865) Tea: enter Mrs Cameron (in funny red open-work shawl) with two of her boys. T. appears, and Mrs C. shows a small firework toy called ‘Pharaoh’s Serpents’, a kind of pastile, which, when lighted, twists about in a worm-like shape. Mrs C. said the were poisonous and forbad us all to touch. T. in defiance put out his hand.

‘Don’t touch ’em!’ shrieked Mrs C ‘You shan’t, Alfred!’ But Alfred did. ‘Wash your hands then!’ But Alfred wouldn’t, and rubbed his moustache instead, enjoying Mrs C.’s agonies. Then she said to him: ‘Will you come tomorrow and be photographed?’ He, very emphatically, ‘No.’

(June 1867) Down train comes in Mrs Cameron, queenly in a carriage by herself surrounded by photographs. We go to Lymington together, she talking all the time, ‘I want to do a large phtograph of Tennyson, and he objects! Says I make bags under his eyes — and Carlyle refuses to give me a sitting, he says it’s a kind of Inferno! The greatest men of the age’ (whith strong emphasis), ‘Sir John Herschel, Henry Taylor, Watts, say I have immortalized them — and these other men object!! What is one to do — Hm?

This is a kind of interrogative interjection she often uses, but seldom waits for a reply.”

“Saturday, 18 August. Ned sketches. I read aloud Robin Hood and the Monk… Ned does not paint down here (It’s his holiday), and only makes a few pencil sketches. He occupies himself, when in the mood, with designs for the Big Book of Stories in Verse by Morris, and has done several from Cupid and Psyche; also pilgrims going to Rome and others. He founds his style in these on old Woodcuts, especially those in Hypnerotomachia, of which he has a fine copy. His work in general, and that of Morris too, might perhaps be called a kind of New Renaissance. “

Description of Dante Gabriel Rossetti

When Dante Gabriel Rossetti came to visit, Allingham made a note in his diary, reminding himself to “Use him nobly while your guest” and to read Rossetti’s Early Italian Poets. At one point during his stay, Allingham observes that DGR didn’t make an effort to leave the sofa all day, so engrossed was he in reading The Mill on the Floss. I love how Allingham describes him so vividly, capturing both his physical presence and his artistic tastes.

“R. walks very characteristically, with a peculiar lounging gait, often trailing the point of his umbrella on the ground, but still obstinately pushing on and making way, he humming the while with closed teeth, in the intervals of talk, not a tune or anything like one but what sounds like a sotto voce note of defiance to the Universe. Then suddenly he will fling himself down somewhere and refuse to stir an inch further. His favourite attitude–on his back, one knee raised, hands behind his head. On a sofa he often, too, curls himself up like a cat.

He very seldom takes particular notice of anything as he goes, and cares nothing about natural history, or science in any form or degree. It is plain that the the simple, the natural, the naive are merely insipid in his mouth; he must have strong savours, in art, in literature and in life. Colours, forms, sensations are required to be pungent, mordant. In poetry he desires spasmodic passion, and emphatic, partly archaic, diction. He cannot endure Wordsworth. He sees nothing in Lovelace’s “Tell me not, Sweet, I am unkind”. In foreign poetry, he is drawn to Dante by inheritance (Milton, by the way, he dislikes); in France he is interested by Villon and some others of the old lyric writers, in Germany by nobody. To Greek literature he seems to owe nothing, nor to Greek art, directly. In Latin poetry he has turned to one or two things of Catullus for sake of the subjects. English imaginative literature — Poems and Tales, here lies his pabulum: Shakespeare, the old Ballads, Blake, Keats, Shelley, Browning, Mrs Browning, Tennyson, Poe being first favourites, and now Swinburne. Wuthering Heights is a Koh-i-noor among novels, Sidonia the Sorceress ‘a stunner’. Any writing that with the least competency assumes an imaginative form, or any criticism on the like, attracts his attention more or less; and he has discovered in obscurity, and in some cases helped to rescue from it, at least in his own circle, various unlucky books; those, for example, of Ebenezer Jones (Studies of Sensation and Event) and Wells, author of Joseph and His Brethren and Stories of Nature. About these and other matters Rossetti is chivalrously bold in announcing and defending his opinions, and he has the valuable quality of knowing what he likes and sticking to it. In Painting the Early Italians with their quaintness and strong rich colouring have magnetised him. In Sculpture he only cares for picturesque and grotesque qualities, and of Architecture as such takes, I think, no notice at all.”

A Passionate Bibliophile

When he expresses his deep passion for the written word, I find an undeniable connection. It’s not necessarily about agreeing or disagreeing on a particular work, but about instantly recognizing that shared passion; a passion I too possess. (I’m sure many of you can relate to that). In 1858, he wrote these thoughts on the work of Robert Browning:

“Too often want a solid basis for R.B.’s brilliant and astounding cleverness. A Blot in the ‘Scutcheon is solid. How try to account for B.’s twists and turns? I cannot. He has been and still is very dear to me. But I can no longer commit myself to his hands in faith and trust. Neither can I allow the faintest shadow of a suspicion to dwell in my mind that his genius may have a leaven of quackery. Yet, alas! he is not solid–which is a very different thing from prosaic. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is as solid as anything in literature; has imaginative coherency and consistency in perfection. Looking at forms of poetic expression, there is not a single utterance in Shakespeare, or of Dante as far as I know, enigmatic in the same sense as so many of Browning’s are. If you suspect, and sometimes find out, that riddles presented to you with Sphinxian solemnity have no answers that really fit them, your curiosity is apt to fall towards freezing point, if not below it. Yet I always end by striking my breast in penitential mood and crying out, ‘O rich mind! wonderful Poet! strange great man!’

One of Allingham’s most consistent friendships was with Thomas Carlyle. He’s mentioned throughout the diaries repeatedly. They frequently discussed literature

In 1871:

“8 November, 1871: With Carlyle. Old Saints. Shakespeare: C. said with emphasis, “The longer I live, the higher I rate that much-belauded man.” He thought that Shakespeare was much impressed with Christianity; to which I demurred. He repeated ‘The cloud-capt Towers’, etc., dwelling once more on We are such stuff as dreams are made of, and out little life, is rounded with a sleep.’–He quoted Richter–‘These words created whole volumes within me,” and mused, saying the words again to himself, ‘such stuff as dreams are made of’.

To my mind, I confess this fine dramatic passage seems of no very particular value when separated from its context.

We agree about Scott as a poet, and, on the whole, about Byron–Moore, too.

Spoke of Gray–the Elegy, Letters from the Lakes, and passed to Goldsmith. At no time did C. show himself so happy and harmonious as when talking on some great literary subject with nothing in it to raise his pugnacity. The books and writers who charmed his youth–to return to these was to sail into sheltered waters.

C. said ‘Writing is an art. After I had been at it some time I began to perceive more and more clearly that it is an art.’ “

1874:

“Of Browning’s Balaustion, C. said ‘I read it all twice through, and found out the meaning of it. Browning most ingeniously twists up the English language into riddles–“There! there is some meaning in this–can you make it out?” I wish he had taken to prose. Browning has far more ideas than Tennyson, but is not so truthful. Tennyson means what he says, poor fellow! Browning has a meaning in his twisted sentences, but he does not really go into anything, or believe much about it. He accepts conventional values. “

While reading the diary, I made note of books mentioned by Allingham in order to compile a reading list:

- The Waverley Novels

- He records which Waverley novels impressed him at the time: Guy Mannering, The Antiquary, Ivanhoe, Kenilworth, The Talisman, then goes on to say in scenes in The Fortunes of Nigel, Quentin Durward, The Fair Maid of Perth, The Pirate, and The Monastery “as vivid as any real experience”.

- The Lady of the Lake and Marmion, both by Sir Walter Scott

- Laurie Todd, or the Settlers in the Wood John Galt

- Brambletye House: Or Cavaliers and Roundheads by Horace Smith

- The Essays of Elia, Charles Lamb

- Poems of Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, Charles Lamb

- Johnson’s ‘Poets’

- Hierarchy of Blessed Angels, Thomas Heywood

- Table Talk and Aids to Reflection, both by Coleridge

- Life, Letters, and Literary Remains of John Keats

- Week on the Concord and Merrimac Rivers, Thoreau

- The Raven, Poe

- A footnote by Allingham’s wife says that in 1850-53 he read Homer, Plato, Plutarch, Meredith’s Poems, Coleridge, Emerson, Gibbon, Dante, Swedenborg, Byron, Barnes, Bacon’s Essays, she notes, “he read and walked every evening.”

- Mr Sludge, “The Medium”, Browning

- Newman’s Apologia

- Ursula Mirouet, Honore de Balzac

- Tennyson’s Maud

- Robin Hood and the Monk

- Folio of Virgil w/plates (read with Burne-Jones during his stay with W.A.)

- Raleigh’s History of the World (also looked at with Burne-Jones)

- As You Like It, Shakespeare (Diary entry: “4 May 1867 Sit under Big Oak reading As You Like It– and this might be Jacque’s very brook in Arden.”)

- Life and Death of Jason, William Morris (W.A. described it as ‘admirable’.)

- May-Day and Other Pieces, given to W.A. from the author, Emerson

- The Mill on the Floss, George Eliot

- The Ring and the Book, Browning

- Frederick the Great, written by his friend Thomas Carlyle. (W.A. referred to it as the ‘reductio ad absurdum’ of Carlyleism and said “open it where you, the page is alive.”)

- Works of Francis Bacon, edited by Spedding

- Jane Eyre

- Vanity Fair

More about the Pre-Raphaelites

- Birth of the Brotherhood

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Romantic Rebel of the Pre-Raphaelites

- John Everett Millais: The Prodigy Who Painted Emotion

- Pre-Raphaelite FAQs

- Pre-Raphaelite List of Immortals

- Pre-Raphaelite Luminosity

- Pre-Raphaelite Women

- What is the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Woman?’

- William Holman Hunt: The Visionary of Pre-Raphaelite Symbolism