by Stephanie Chatfield

Women are at the heart of Pre-Raphaelite art, giving rise to the enduring idea of the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Woman.’ The term often appears in media today to describe actresses or musicians with long, flowing hair. Musician Florence Welch being a frequent example and proud embodiment of the look.

But was there ever a single ideal? When we look beyond the painted canvases to the real women who inspired them, we find a rich diversity. To their credit, the Pre-Raphaelites and their circle didn’t idealize just one type. Women of varying shapes, features, and presence became muses. Over time, their individual strengths have blended into the image we now call the ‘Pre-Raphaelite Stunner.’

While I’m wary of reducing any woman to her appearance alone, exploring how these models helped shape a visual legacy can offer meaningful insight into the aesthetic we associate with ‘Pre-Raphaelite.’

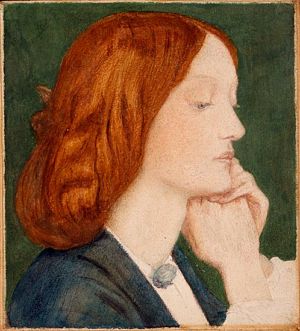

Elizabeth Siddal

Elizabeth Siddal was one of the earliest and most iconic Pre-Raphaelite models. Discovered while working at Mrs. Tozer’s millinery shop, she made her first appearance in Walter Howell Deverell’s painting Twelfth Night. Soon after, she posed for William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, most famously as Ophelia. Eventually, Siddal became the exclusive muse of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The artist also took her on as a pupil as she began a promising artistic career of her own. Their passionate, on-again-off-again relationship spanned nearly a decade before they finally married in 1860.

Siddal’s life, however, was marked by physical and emotional suffering. Often described as fragile, she became addicted to laudanum, an opiate commonly used at the time. The stillbirth of her daughter deepened her depression, and in 1862, Siddal died of an overdose.

Seven years later, in artistic desperation, Rossetti had her grave exhumed to retrieve a manuscript of poems buried with her. That act cast a lasting shadow of tragedy and macabre fascination over Siddal’s legacy.

Yet at the beginning, it was her face and presence that deeply inspired Rossetti. His sister, poet Christina Rossetti, captured this devotion in her poem In an Artist’s Studio. As one line puts it: ‘He feeds upon her face by day and night.’

Ford Madox Brown dubbed Rossetti’s drawings of Siddal a “monomania,” and Rossetti himself wrote that seeing her defined his destiny. Her features soon dominated his art throughout the 1850s, shaping the Pre-Raphaelite ideal.

Elizabeth Siddal did not fit the mold of conventional Victorian beauty. At a time when a petite, delicate frame was idealized, she was considered somewhat tall. Red hair, too, was unfashionable and was often seen as a sign of bad luck or unattractiveness. Yet Siddal’s vivid hair became a hallmark of Pre-Raphaelite art. Rossetti and his peers portrayed her flowing red locks with such romantic intensity that they helped redefine its aesthetic appeal.

In the years after her death, Siddal’s hair took on an almost mythical status. Charles Augustus Howell claimed that when she was exhumed, her hair had continued to grow. filling the casket with fiery strands. Though biologically impossible, the story endured, becoming part of the eerie and enduring legend that surrounds the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

While Rossetti was captivated by Elizabeth Siddal’s features, it’s equally compelling to consider how Siddal saw herself.

Her self portrait reflects the Pre-Raphaelite commitment to truth in nature. It stands apart from the idealized images of women often associated with the movement. Siddal presents herself with honesty and directness, an unflinching portrayal that resists romanticization.

Annie Miller

Annie Miller was a muse to artist William Holman Hunt and appeared in some of the earliest Pre-Raphaelite works. Hunt intended to marry her and arranged for her to receive lessons in refinement, hoping to elevate her social standing. Their relationship became strained, especially during his extended trip to the Middle East, and the marriage never happened.

Frustrated by what he saw as her inappropriate behavior, Hunt later erased Miller’s likeness from many paintings, including The Awakening Conscience and Il Dolce Far Niente. As a result, Rossetti’s portrayals are what keep her presence in the Pre-Raphaelite story alive; the images I’ll share below..

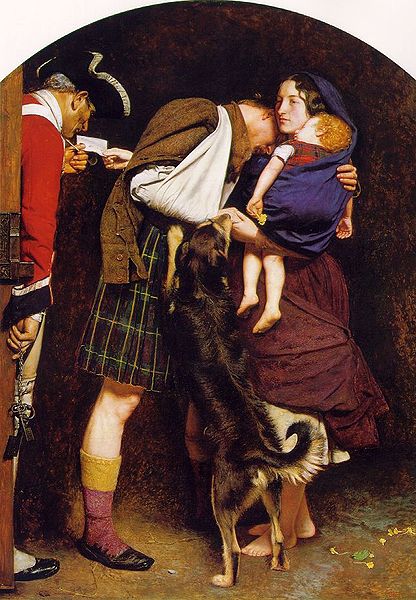

Effie Millais

Effie Gray was trapped in a cold, unconsummated marriage to critic John Ruskin when she met John Everett Millais. After a painful annulment, requiring her to prove her virginity, she and Millais were finally free to marry.

Emma Thompson wrote and starred in a film about Effie’s story, with Dakota Fanning playing Effie Gray.

Fanny Cornforth

Fanny Cornforth may have been Rossetti’s truest and most loyal companion. Often dismissed or disparaged by those in his inner circle, she nonetheless remained steadfast. Her arrival ushering in a new, sensuous phase of his work, most notably with Bocca Baciata (The Kissed Mouth).

In contrast to Elizabeth Siddal’s frequent illnesses, Cornforth was vibrant, full-figured, and full of life. Yet despite her closeness to Rossetti, she was not the woman he would marry.

Over time, her role shifted from muse to housekeeper as Rossetti’s artistic focus turned to other faces. Still, she remained a constant presence in his life, a living reminder of an era of joy and creative freedom. I highly recommend reading Stunner: The Fall and Rise of Fanny Cornforth by Kirsty Stonell Walker.

Georgiana Burne-Jones

Georgiana Burne-Jones became engaged to Edward Burne-Jones, whom she lovingly called ‘Ned,’ while still in her teens. Known for her gentle nature and devotion, she remained a supportive partner throughout his life and career.

Known as “Georgie,” she was the fifth of eleven MacDonald children. Her sister Agnes married painter Edward Poynter, while Louisa became Stanley Baldwin’s mother and Alice gave birth to Rudyard Kipling.

Maria Zambaco

Despite his devoted marriage to Georgiana, Burne-Jones had a major affair with Maria Zambaco. As things turned turbulent, his depictions of her took on deeper, conflicted tones.

Jane Morris

Jane Morris entered the Pre-Raphaelite circle in Oxford, catching the attention of Rossetti and Burne-Jones during a theater performance.

She married William Morris, Rossetti’s close friend, yet later began a passionate relationship with Rossetti. Their story endures, made all the more striking by Morris’s unwavering support of her, despite his pain.

Rossetti’s paintings of Jane took on the same obsessive quality that characterized his earlier works with Elizabeth Siddal. Once again, the artist’s fixation is channeled through the image of his muse.

Alexa Wilding

Rossetti noticed Alexa Wilding on a bustling street and promptly asked her to model for him. Tall and strikingly different from his muse Jane Morris, Alexa’s physical features were a distinct contrast.

Kirsty Stonell Walker has crafted a captivating fictionalized account of Alexa’s life in A Curl of Copper and Pearl. It’s a fascinating a glimpse into the world of this enigmatic muse..

What about Pre-Raphaelite beauty in today’s woman?

It may seem like I’m pitting these women against one another by their looks, but that’s not my aim. I want to show that our idea of Pre-Raphaelite beauty is really an amalgamation.

The varied tastes of the Pre-Raphaelites combined to create the bold, beautiful look we now associate with the Pre-Raphaelites.

It’s an inspiring notion: the Pre-Raphaelite ideal grew from many women, and so does the world. In that sense, we’re all Stunners.

Break free from society’s limited standards of beauty. Embrace your unique strengths and quiet the inner critic that tries to hold you back. Together, we can celebrate the diverse beauty that makes up our world.

More about the Pre-Raphaelites

- Birth of the Brotherhood

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Romantic Rebel of the Pre-Raphaelites

- John Everett Millais: The Prodigy Who Painted Emotion

- Pre-Raphaelite FAQs

- Pre-Raphaelite List of Immortals

- Pre-Raphaelite Luminosity

- Pre-Raphaelite Women

- The Diaries of William Allingham

- William Holman Hunt: The Visionary of Pre-Raphaelite Symbolism